Why Doctors And Nurses’ Mental Health Is At Risk

Why Doctors And Nurses’ Mental Health Is At Risk https://kupplin.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/health-professional-team_52683-36185.jpg 626 417 kupplinadmin kupplinadmin https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/6eec4427dd031e16c8da4c63019a7497?s=96&d=mm&r=g- kupplinadmin

- no comments

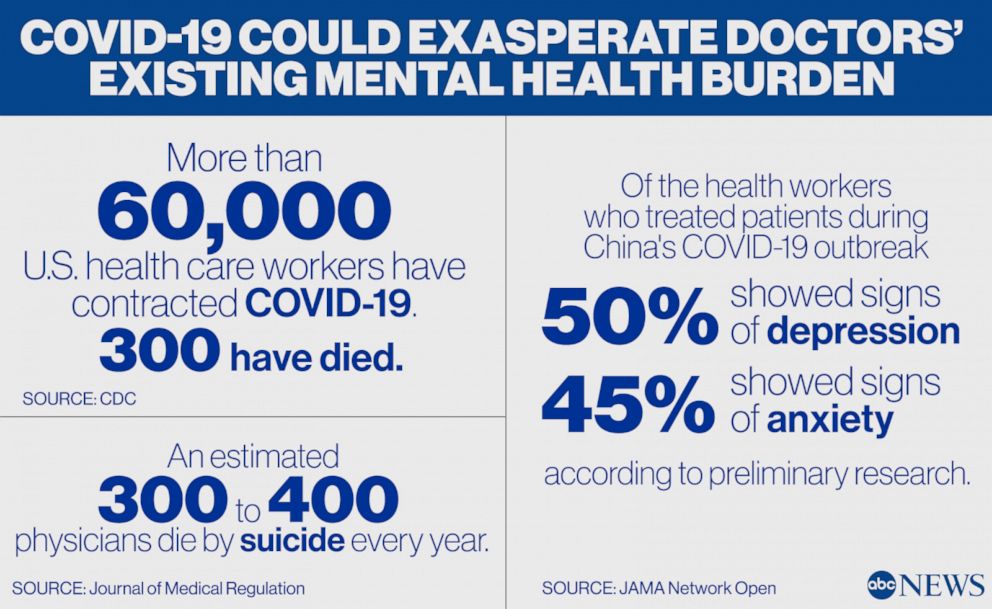

The coronavirus pandemic has taken a toll on the American psyche, with a third of Americans now showing signs of clinical depression or anxiety, a rate twice as high as before the pandemic, according to Census Bureau data. Those grim statistics are likely even direr for the health care workers on the front lines of the crisis, experts say.

While it’s too early to truly quantify the effect that treating patients under combat-like conditions will have on doctors in the coming months or years, preliminary research out of China highlights the mental health risk that American health care workers potentially face.

But Why do the doctors have to go through this?

“Health care workers are not starting with a baseline of zero. They had super elevated depression, suicide rates, and burnout prior to COVID,” explained Dr. Jessica Gold, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis.

Depression, burnout, and suicide plague the medical profession. While there hasn’t been much recent research evaluating the incidence of physician suicide in the United States, studies from the 1990s found that the risk for suicide among male physicians was 40% higher than for men in the general population. For female physicians, that risk was 130% higher.

Newer research continues to indicate that suicide rates among physicians outpace rates in the general public.

Layered on top of an already stressful job is a public health emergency the likes of which our country hasn’t seen in a century, compounding doctors’ existing mental health risks.

The list of stressors for health care workers during COVID-19 is overwhelming even to read. They worried about not having enough PPE to protect themselves from the virus. They agonized over the prospect of running out of ventilators and having to withhold care from the dying. Many practiced outside of their field. They took on grueling shifts, with no sense of when the outbreak would crest. Burnout was brutal, they said. Colleagues fell ill and some died — 63,000 and nearly 300 respectively according to the CDC. After finishing their COVID-19 duty, some were redeployed. They slept in hotels, isolated, to protect their families, or went home each night, and worried about putting their families at risk. Those far away from the front lines said they felt guilty and inadequate for not being there.

Then there was the helplessness inherent in being unable to save tens of thousands of patients.

Trauma From COVID-19 Could Drastically Hurt Doctors’ Mental Health

Dr. Jo Shapiro’s job is taking doctors’ mental health and well-being seriously.

After three decades of practicing surgery, Shapiro spent 10 years at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts, directing a program to train physicians to support one another when they experience trauma on the job. She’s given peer support training at more than 50 organizations in the United States and around the world, and when the pandemic hit there was even more interest among organizations who wanted to launch new programs or adapt their existing framework to the COVID-19 crisis.

But when Shapiro herself developed COVID-19 early on, she refused to take her own advice about self-care and self-sacrifice.

“Although I didn’t have to end up in the hospital, I have never been that sick,” she said. As her health worsened, Shapiro continued to work on starting peer support programs when organizations reached out to her.

“The level of hypocrisy that I demonstrated to myself as I was getting sicker and sicker shows you how deep the culture is. I was doing exactly what I tell people not to do,” she said.

The stigma attached to asking for support can lead doctors to suffer in silence or use negative coping mechanisms, like alcohol or drugs to self-medicate, experts say.

“Nobody wants to look like they are incompetent or like you can’t trust them in a battle,” said David Pezenik, a licensed clinical social worker, who counseled first responders about grief and trauma after 9/11.

“It usually takes a little while for it to set in and manifest,” he said of trauma.

“The patient might not even realize what they’re going through. The first part, before a denial is a shock. When you’re in shock you don’t even feel the pain.”

“If we look at the United States broadly, a tiny handful of places are taking this as seriously as they should be. That’s grossly inadequate to take care of the huge number of health care providers who are facing this,” Meltzer-Brody said.

There needs to be a call to arms that doctors’ mental health needs are not being met

- Post Tags:

- Mental Health of Doctors

- Posted In:

- Uncategorized

Leave a Reply